The Sound of Music

How Does Music Sound To Me?

Ben Bennetts

Background

I have listened to and enjoyed music all my life. The interest was sparked by the early rock and roll greats of the late ‘50s, early ‘60s. Performers such as Buddy Holly, Gene Vincent, Elvis Presley (his early music), the Everly Brothers, Bill Haley, Fats Domino and so on got me started. I was then introduced to classical music at my boarding school in the late ‘50s when I joined an after-class music appreciation society. From these two vantage points, rock and roll and classical music, I expanded my musical interests and as I travelled around the world during my professional years, I collected all sorts of music. I estimate that I have around 1,400 CDs in my collection; half classical, the rest a mix of jazz, world, ambient, percussion, trance, hip-hop, popular and other forms of progressive and modern music.

And then tragedy struck. As I entered my sixtieth decade, my hearing started to go down. I accepted it as a sign of advancing years and started wearing BTE aids. They helped, but to my great disappointment, I discovered I could no longer enjoy music, with or without the aids. All music, live or recorded, became distorted. I could no longer whistle a simple tune, such as Happy Birthday. I could no longer enjoy any of my CDs. I began investigating the cause. I had an MRI scan. Maybe something was wrong inside my head—dead frequency zones in the cochlea, a damaged auditory nerve, a brain tumour? Nothing serious was revealed. As part of my investigation, I read about research going on at Cambridge University, contacted the group, and ultimately made three visits. Here’s what happened.

The Experiment

In 2012, I visited a PhD student, Marina Salorio-Corbetto, in the Auditory Perception Group in the Department of Experimental Psychology at Cambridge University. At the lab, I was introduced to Professor Brian Moore. Brian is the leader of the Auditory Perception Group and during our brief discussion he asked me to describe how music sounds to me—”What do you hear?” he asked. This was a tough question and my reply at the time was flippant—”A cacophony”—and devoid of any meaningful content. Subsequently, I pondered on how to answer this question more accurately and on my return, I conducted an experiment. I selected around twenty of my CDs and played samples from them on my Bose Lifestyle 20 music system. I kept my hearing aids in place (Phonak Nathos MW behind-the-ear aids) rather than listen to the music either with my hearing aids removed (I would not be able to hear much unless the volume was at full blast), or through headphones (which would again mean removing my hearing aids). Here’s a summary of the results.

Results: Classical

I tried old favourites such as a couple of Beethoven Symphonies: the 5th (the Allegro, first movement) and 9th (the Presto ‘Ode to Joy’, last movement). I followed this with lighter music—Vivaldi’s mandolin concertos, classical guitar music composed by Fernado Sor and Robert de Visée, Telemann’s trumpet concertos, Dvořák’s From the New World, some Spanish Renaissance music (lute, vihuelas, guitar and female voice), and something more savage: Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, an all-time favourite of mine. In all cases, I would not have recognised the music in a ‘blind’ hearing. I tried hard to recreate the music in my head from memory but it was extremely difficult to match memory with what was being received and processed by whatever part of the brain does this. Notes did not go up and down as they should and in many cases the base lines dominated anything that was happening at higher frequencies. Then I turned to other styles of music.

Results: Non-Classical

Drums and drum music have long been a passion of mine and I dredged up several CDs containing predominantly drum music, starting with a Dutch percussion group called Slagerij van Kampen performing on an album called Tan. Here, I had more success. I could make out the beat and also the transition and juxtapositioning of the drums.

Moving on from this, I tried other drum music—a Japanese group called Ondekoza, a Mission into Drums, a compilation of different trance-ambient artists who focus their music around a repetitive drum beat, an early 1986 electronic style recording called Transfer Station Blue by Michael Shrieve who used an electronic drum to create a sharp rhythmic beat, rich in pulse-punctuated full-frontal higher frequencies.

From here I moved on to more lush electronic music—albums such as Suave by B-Tribe (flamenco music mixed with trip-hop and ambient), Suzuki by Tosca (Dorfmeister and Huber, two early exponents of what we nowadays call ambient music); Big Calm by Morcheeba; Moodfood by Moodswings (featuring the pure voice of Chrissie Hynde), Sanchez and Mouquet’s Deep Forest, Gevecht met de Engle (Battle with the Angel) by another Dutch group, Flairck, and, finally, one of my jazz CDs, an album called Blue Camel by the Lebanese oud player Rabih Abou-Khalil.

All were lost on me. Even with my musical memory, I could no longer appreciate the music.

Conclusion

I tried to be objective in my answer to the question, “What do you hear?” By its very nature, the answer is difficult to express in unambiguous objective scientific terms. We hear what we hear and if it’s pleasurable, fine. If it’s not pleasurable, also fine. We just don’t like it. But, if it’s not pleasurable, whereas once it was, not fine. I would like to know why listening to music is no longer pleasurable and why I can no longer recall complex tunes in my head. Even if I can’t fix the problem, it would be good to know its root cause.

Marina, the PhD student working in Professor Brian Moore’s department, did send me a summary of her findings. Basically, she said that my hearing loss had affected my ability to use temporal fine structure information which, in turn could affect pitch perception in both speech and music. She also suggested that my hearing loss has modified my frequency selectivity and that my auditory filters were wider than normal. Apparently, both deficits are common when you have a cochlear hearing loss but, contrary to my own thoughts, she could not find any dead regions in my cochleas.

So there you have it. I am still working at understanding the physiological behaviour that underpins temporal fine structure and auditory filters but this is taking me deep into the realms of how the ear works and how aural data is processed by the brain and, quite frankly, is currently beyond me. I accept that my ability to hear and enjoy music correctly will never return; there is no cure for what ails me, more’s the pity.

Footnote

In my initial answer to Brian Moore, I also said that music, to me, these days sounds just as if it had been played by the defunct Portsmouth Sinfonia. This orchestra, founded in 1970, was comprised of people who were either non-musicians or, if they were musicians, were asked to play an instrument with which they were unfamiliar. They were also asked to do the best they could rather than deliberately play out of tune. Their first recording became a surprise hit and they continued playing until they disbanded in 1979. You can sample the sound of this orchestra on YouTube. Enter ‘Portsmouth Sinfonia’ into Google and see where it takes you.

If you do this, the renditions you will hear are extremely close to what I now hear when I play correctly-played classical and non-classical music. But, there’s an interesting paradox here. When I listen to the Portsmouth Sinfonia on YouTube, am I hearing what they actually played or am I hearing a distorted version of what they played? A distorted version of music that is already distorted? I will never know the answer to this question but I have to admit, I collapsed with laughter today when I listened to Also sprach Zarathustra, Richard Strauss’s stirring music used to herald the start of Stanley Kubrick’s movie 2001, A Space Odyssey. The Portsmouth Sinfonia’s version of this piece of music encapsulates the meaning of what I meant when I described my listening experience to be a cacophony.

Note: this article is a summary of a much longer article with the same title that delves more into what I heard when I conducted my experiment. You can download the full article here.

If you would like to contact Ben about his experiences, email ben@ben-bennetts.com

If you would like to share your own experiences of listening to music with a hearing loss, do get in touch with us on: musicandhearingaids@leeds.ac.uk

Despite being branded as tone deaf in schooldays, and suffering from moderate hearing loss too, seven years ago I started to play trombone. Now, aged 69, I play in a brass band. My wife, Carol, a lifelong musician who plays euphonium is afflicted with a severe hearing loss as well, a long term condition combined with severe tinnitus.

Despite being branded as tone deaf in schooldays, and suffering from moderate hearing loss too, seven years ago I started to play trombone. Now, aged 69, I play in a brass band. My wife, Carol, a lifelong musician who plays euphonium is afflicted with a severe hearing loss as well, a long term condition combined with severe tinnitus. Players should be able to clearly hear neighbouring players, so as to be able to play in time and in tune with one another. They also need to hear other sections of the band to effect the overall tuning and timing of the music. As a trombone player, I need to be able to hear euphonium and baritone horns immediately in front, to perceive the higher pitched sounds of the cornets from the far side of the band, to be aware of the horns, all whilst not forgetting the basses (tubas) which are hard to ignore. And in rehearsal, it is important of course to hear the instructions from the conductor!

Players should be able to clearly hear neighbouring players, so as to be able to play in time and in tune with one another. They also need to hear other sections of the band to effect the overall tuning and timing of the music. As a trombone player, I need to be able to hear euphonium and baritone horns immediately in front, to perceive the higher pitched sounds of the cornets from the far side of the band, to be aware of the horns, all whilst not forgetting the basses (tubas) which are hard to ignore. And in rehearsal, it is important of course to hear the instructions from the conductor! For me, playing without hearing aids is not a realistic option. With my high frequency loss, I am barely aware of the cornet sounds and much of the articulation is lost. The resultant dead and rather woolly musical environment, with no perception of commands from the conductor would preclude participation.

For me, playing without hearing aids is not a realistic option. With my high frequency loss, I am barely aware of the cornet sounds and much of the articulation is lost. The resultant dead and rather woolly musical environment, with no perception of commands from the conductor would preclude participation. Carol uses two Phonak Nathos SP aids with features such as the frequency translation of higher pitched sounds, enabling her to comprehend some of those missing high frequency sounds. Early experience with these aids suggested that she had trouble precisely pitching and playing in tune and this was particularly evident if playing in a small ensemble. Fortunately, the enabling of a music program, disabling some features of the aids, made a dramatic difference and in the small ensemble she was able to play far more reliably in tune. However, in band a major problem unfolded whereby when playing her euphonium, especially when accompanied by a neighbouring euphonium, she could hear virtually nothing of the rest of the band. This problem intrigued me and I set about trying to find why the euphonium was so troublesome!

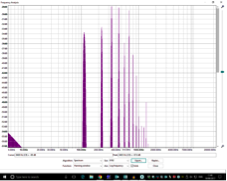

Carol uses two Phonak Nathos SP aids with features such as the frequency translation of higher pitched sounds, enabling her to comprehend some of those missing high frequency sounds. Early experience with these aids suggested that she had trouble precisely pitching and playing in tune and this was particularly evident if playing in a small ensemble. Fortunately, the enabling of a music program, disabling some features of the aids, made a dramatic difference and in the small ensemble she was able to play far more reliably in tune. However, in band a major problem unfolded whereby when playing her euphonium, especially when accompanied by a neighbouring euphonium, she could hear virtually nothing of the rest of the band. This problem intrigued me and I set about trying to find why the euphonium was so troublesome! All brass instruments have characteristic spectral properties, whereby the fundamental of a note with a particular set of overtones gives the instrument its sound. The different instruments differ in size (from the tiny soprano cornet to the large B-flat tuba) and in construction with the size and degree of taper in the bore. The trombone is a parallel bore instrument, and this reflects in the sound which is rich in overtones – the FFT analysis here shows peaks extending to the 15th or even 20th harmonic of the note being played. Curiously, the trombone can seemingly be very light on the fundamental of the note being played. In contrast, the euphonium with its taper bore is very strong in the fundamental, with the overtones rapidly dying away. The similarly pitched baritone horn with a less tapered bore has a spectrum more like that of the trombone.

All brass instruments have characteristic spectral properties, whereby the fundamental of a note with a particular set of overtones gives the instrument its sound. The different instruments differ in size (from the tiny soprano cornet to the large B-flat tuba) and in construction with the size and degree of taper in the bore. The trombone is a parallel bore instrument, and this reflects in the sound which is rich in overtones – the FFT analysis here shows peaks extending to the 15th or even 20th harmonic of the note being played. Curiously, the trombone can seemingly be very light on the fundamental of the note being played. In contrast, the euphonium with its taper bore is very strong in the fundamental, with the overtones rapidly dying away. The similarly pitched baritone horn with a less tapered bore has a spectrum more like that of the trombone.

Going back in time: hearing aids through the decades

Going back in time: hearing aids through the decades