Some practical tips for audiologists and listeners

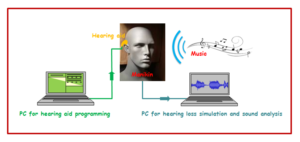

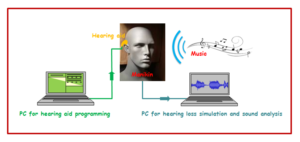

In January 2016 we attended a seminar on the effects of advanced hearing aid features at Cardiff Metropolitan University. This was a useful opportunity to hear from world renowned speakers on the science behind challenges with listening to music with hearing aids, feedback and practical tips from the clinical world and also insights into the benefits and limitations of hearing aid technology.

We heard from Professor Brian Moore on the effects of both hearing loss and hearing aids on music perception and from Marshall Chasin on fitting aids for musicians. We were reminded that damage to the inner ear is not always obvious in relation to the audiogram. The Audiogram (a hearing test) is a very broad way of testing hearing and for Noise induced hearing loss (NIHL), a person may even have a normal audiogram but with underlying damage to the inner ear that causes difficulties in discriminating sounds (for more on Hidden Hearing Loss, see Chris Plack’s recent BSA seminar). To perceive music well we need to be able to discriminate a much wider range of frequencies than is tested with an average hearing test.

Another relevant point for listening is that with hearing loss, as well as losing the ability to pick out specific sounds we also have poorer localisation skills or abilities to tell where sound is coming from. For music this can be really important in separating sounds out from a mixed musical signal of several instruments or voices.

Specifically with hearing aids, multi-channel aids can flatten the spectrum of the musical signal which can make it harder to identify instruments. A recent paper by Madsen, Stone, McKinney, Fitz & Moore (2015) explored the effects of wide dynamic range compression on identifying instruments and identified lower reports of clarity when using WDRC versus linear amplification. The effects of slow versus fast compression are more complex and may relate to the type of music being listened to.

There are pros and cons of both fast acting and slow compression. Slow acting compression can facilitate being able to pick out the main tune/instrument when louder backing sounds are there, which otherwise might cause the hearing aid to cut sounds levels down too quickly. However, it does not restore loudness perception to ‘normal’ and is not good if various sources are at different levels. In the time it takes to recover, we can miss dynamic changes in music. Overall the consensus of opinion was that there seems to be a preference for slow compression versus fast acting compression for music but this is very dependent on setting and type of music being listened to (Moore & Sek, forthcoming).

Other Considerations for fitting aids:

In terms of microphones, directional microphones can be useful, and can help to pick out specific instruments in the presence of competing sounds. However, they can also make things worse by reducing ability to hear the separation of sounds (where sounds are located and that they are coming from separate sources); again, this depends on the listening setting.

Low Frequency (LF) gain: The limited LF in the Hearing aid bandwidth can also be a problem as we don’t get amplification of the lower pitches and the LF range of music exceeds the typical range we are concerned with for speech. The LFs are limited on purpose for speech to prevent LF masking where the low frequency sounds potentially cover over the speech sounds.

In this regard consider open fitting where possible as a preference so there is natural acoustic use of LF where hearing is good for these frequencies. Music tends to be louder than speech so even with some mild LF loss we may well still hear the LF cues effectively without needing amplification from the hearing aid. Go for as wide a bandwidth as possible in the aid, again as the range of musical sounds tends to exceed that of speech.

Many aids have frequency lowering technology available but this can introduce inharmonicity where high and low harmonics are out of tune. This was considered manageable over 2 kHz as listeners with high frequency (HF) hearing loss may be unlikely to detect the mistuning with high harmonics.

Smoothing the peaks in frequency response during the fitting may help, though more evidence is needed for this. Feedback cancellation can also be problematic as it can mistake musical tones for feedback. Where there is frequency shifting involved this may potential alter perception of pitch and or harmonics.

The peak input limiting level of aids are a significant problem; we know music typically has a wider and higher dynamic range than speech and peak input limiting levels below 105dB simply mean we lose some of the input signal for music resulting in poor sound quality. We were played examples of this in the seminar down to 92dB peak input limiting and the effects were very obvious. Whilst for speech anything above 85dB is likely not to be problematic, this is not the case for music and we cut out an awful lot by the aid being optimised for speech (to hear for yourself, click here)

One issue for these factors in hearing aid fittings is that we don’t always have access to all these areas transparently in the fitting software or on the specification sheet. In some cases it is hard to know exactly what and how the aid is affecting input or rather what algorithms are in use. Changes to compressions that used to be more obvious may be in the fitting tools but without specific parameters and it may be that clinicians will need to ask manufacturers more about what the aid is doing so that we can optimise for individual listeners.

Strategies for fitting:

NB: remember in the music program not the speech program

Consider slow compression

Higher input peak limiting

Take off feedback manager

Use open fitting where possible

Turn off frequency transpositions

Turn off noise reduction algorithms

Set OSPL90 6dB lower than for speech

If possible, play some musical scales in the clinic and check listener can hear each note

Choose the widest available bandwidth for mild losses; consider using a narrower HF bandwidth for HL >60dB HL, and for steeper slopes to test for cochlear dead regions where patients are reporting specific discrimination problems.

Strategies for listening

When listening to recorded music – lower volume on the sound source and increase the volume on the aid

Consider use of Assistive Listening Devices (ALDs) such as using FM system as input or streamers, loop or direct audio input (DAI). Connevans have a range of ALDs that may be helpful.

Use scotch tape to cover the hearing aid microphone (this provides 10-12dB attenuation up to 4,000Hz)

Also consider whether a listener with lower degrees of loss is actually better without hearing aids for music listening given the overall louder dynamics of music.

This event was attended by Harriet Crook and Alinka Greasley.

References

Chasin, M. & Hockley, N. S. (2014). Some characteristics of amplified music through hearing aids. Hearing Research, 308, 2-12.

Madsen, S. M. K., Stone, M. A., McKinney, M. F., Fitz, K. & Moore, B. C. J. (2015). Effects of wide dynamic-range compression on the perceived clarity of individual musical instruments. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America, 137, 1867-1876.

Moore, B.C.J. & Sek, A. (2015). Comparison of the CAM2A and NAL-NL2 hearing-aid fitting methods for participants with a wide range of hearing losses. International Journal of Audiology, 55(2), 1-8.

Get in touch

If you have any thoughts, please email the project team:

musicandhearingaids@leeds.ac.uk

You can also get updates about the project and information about music and deafness on our twitter feed @musicndeafness.

Despite being branded as tone deaf in schooldays, and suffering from moderate hearing loss too, seven years ago I started to play trombone. Now, aged 69, I play in a brass band. My wife, Carol, a lifelong musician who plays euphonium is afflicted with a severe hearing loss as well, a long term condition combined with severe tinnitus.

Despite being branded as tone deaf in schooldays, and suffering from moderate hearing loss too, seven years ago I started to play trombone. Now, aged 69, I play in a brass band. My wife, Carol, a lifelong musician who plays euphonium is afflicted with a severe hearing loss as well, a long term condition combined with severe tinnitus. Players should be able to clearly hear neighbouring players, so as to be able to play in time and in tune with one another. They also need to hear other sections of the band to effect the overall tuning and timing of the music. As a trombone player, I need to be able to hear euphonium and baritone horns immediately in front, to perceive the higher pitched sounds of the cornets from the far side of the band, to be aware of the horns, all whilst not forgetting the basses (tubas) which are hard to ignore. And in rehearsal, it is important of course to hear the instructions from the conductor!

Players should be able to clearly hear neighbouring players, so as to be able to play in time and in tune with one another. They also need to hear other sections of the band to effect the overall tuning and timing of the music. As a trombone player, I need to be able to hear euphonium and baritone horns immediately in front, to perceive the higher pitched sounds of the cornets from the far side of the band, to be aware of the horns, all whilst not forgetting the basses (tubas) which are hard to ignore. And in rehearsal, it is important of course to hear the instructions from the conductor! For me, playing without hearing aids is not a realistic option. With my high frequency loss, I am barely aware of the cornet sounds and much of the articulation is lost. The resultant dead and rather woolly musical environment, with no perception of commands from the conductor would preclude participation.

For me, playing without hearing aids is not a realistic option. With my high frequency loss, I am barely aware of the cornet sounds and much of the articulation is lost. The resultant dead and rather woolly musical environment, with no perception of commands from the conductor would preclude participation. Carol uses two Phonak Nathos SP aids with features such as the frequency translation of higher pitched sounds, enabling her to comprehend some of those missing high frequency sounds. Early experience with these aids suggested that she had trouble precisely pitching and playing in tune and this was particularly evident if playing in a small ensemble. Fortunately, the enabling of a music program, disabling some features of the aids, made a dramatic difference and in the small ensemble she was able to play far more reliably in tune. However, in band a major problem unfolded whereby when playing her euphonium, especially when accompanied by a neighbouring euphonium, she could hear virtually nothing of the rest of the band. This problem intrigued me and I set about trying to find why the euphonium was so troublesome!

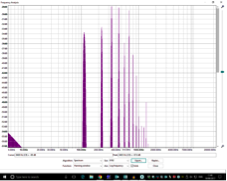

Carol uses two Phonak Nathos SP aids with features such as the frequency translation of higher pitched sounds, enabling her to comprehend some of those missing high frequency sounds. Early experience with these aids suggested that she had trouble precisely pitching and playing in tune and this was particularly evident if playing in a small ensemble. Fortunately, the enabling of a music program, disabling some features of the aids, made a dramatic difference and in the small ensemble she was able to play far more reliably in tune. However, in band a major problem unfolded whereby when playing her euphonium, especially when accompanied by a neighbouring euphonium, she could hear virtually nothing of the rest of the band. This problem intrigued me and I set about trying to find why the euphonium was so troublesome! All brass instruments have characteristic spectral properties, whereby the fundamental of a note with a particular set of overtones gives the instrument its sound. The different instruments differ in size (from the tiny soprano cornet to the large B-flat tuba) and in construction with the size and degree of taper in the bore. The trombone is a parallel bore instrument, and this reflects in the sound which is rich in overtones – the FFT analysis here shows peaks extending to the 15th or even 20th harmonic of the note being played. Curiously, the trombone can seemingly be very light on the fundamental of the note being played. In contrast, the euphonium with its taper bore is very strong in the fundamental, with the overtones rapidly dying away. The similarly pitched baritone horn with a less tapered bore has a spectrum more like that of the trombone.

All brass instruments have characteristic spectral properties, whereby the fundamental of a note with a particular set of overtones gives the instrument its sound. The different instruments differ in size (from the tiny soprano cornet to the large B-flat tuba) and in construction with the size and degree of taper in the bore. The trombone is a parallel bore instrument, and this reflects in the sound which is rich in overtones – the FFT analysis here shows peaks extending to the 15th or even 20th harmonic of the note being played. Curiously, the trombone can seemingly be very light on the fundamental of the note being played. In contrast, the euphonium with its taper bore is very strong in the fundamental, with the overtones rapidly dying away. The similarly pitched baritone horn with a less tapered bore has a spectrum more like that of the trombone.